Job advertisements, recruitment and the culture of full-time working in municipal health and care services

-

English summary of Fafo-rapport 2021:25

-

Leif E. Moland og Ketil Bråthen

-

07 September 2021

This R&D report is the first deliverable in a project describing local authorities’ job advertising practices within the health and care sector, and what steps local authorities can take to increase the percentage of full-time jobs being advertised. The next deliverable will be a tool that local authorities can use in the practical recruitment work. The report gives a practical description of local authorities’ job advertising and recruitment practices, with a view to elucidating why it is as it is, and discusses the prerequisites for changing such practices. The report concludes with suggestions for how local authorities can advertise more full-time positions. The following research questions formed the basis of the work

- What is the procedure for advertising a new external position?

- What is the procedure for advertising internal positions?

- How are policy measures concerning the culture of full-time working incorporated into local authorities’ recruitment strategies?

- What part do the social partners play in these processes?

- What are the main structural and cultural barriers to advertising full-time positions?

- What are the main characteristics of the local authorities that advertise the most full-time positions?

- What will it take to change job advertising practices such that full-time positions become the norm?

Method

In order to shed light on the issues in question, we have reviewed relevant documents from 40 local authorities and conducted a nationwide, online survey of 1981 managers and trade union representatives in the local authorities, with a response rate of 34 per cent. Data on full-time equivalent (FTE) percentages were retrieved from the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities’ PAI (Personnel Administration Information) register, which consists of information on municipal employees’ salaries, sick leave, job codes and hours of work. Data on job advertisements for nursing associates and registered nurses in recent years were obtained from the job databases of the Norwegian Union of Municipal and General Employees (NUMGE) and the Norwegian Nursing Association (NSF). Interviews were also conducted with managers, trade union representatives and HR staff in seven reference local authorities. In three of these, we also followed specific recruitment processes and attended interviews with job applicants.

Main findings

Are job advertising practices in the local authorities a barrier to the culture of full-time working? This is the main question in this study, and the answer is yes. The explanation is partly a reflection of job advertising practices and partly of the underlying factors that make it difficult to advertise full-time positions in situations where the local authority actually wants to be able to do so.

Multiple stages in the recruitment process

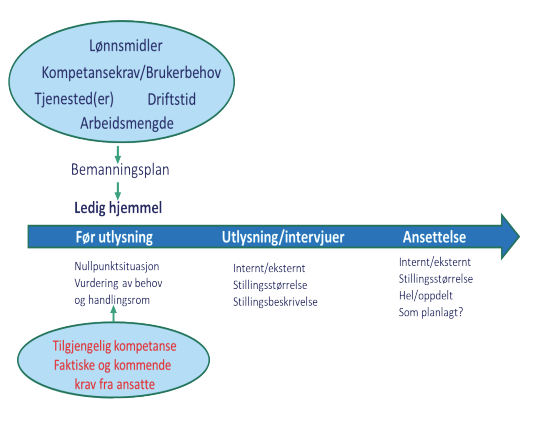

The figure below shows the three stages of the job advertising and recruitment process. First, the local authority identifies its need to recruit someone, then in the second stage, the vacant position is advertised and job applicants are contacted. The third stage leads to an outcome, hopefully an appointment in line with the job advertisement.

The job advertising process: from identifying needs and possibilities to appointment.

Translation of Norwegian words used in the figure

|

Lønnsmidler

|

Financial resources

|

|

Kompetansekrav/Brukerbehov

|

Competence criteria/User needs

|

|

Tjenestested(er)

|

Department(s)

|

|

Driftstid

|

Working period

|

|

Arbeindsmengde

|

Workload

|

|

Bemanningsplan

|

Staffing plan

|

|

Ledig hjemmel

|

Available mandate

|

|

Før utlysning

|

Prior to advertising

|

|

Utlysning/intervjuer

|

Advertising/interviews

|

|

Ansettelse

|

Appointment

|

|

Nullpunktsituasjon

|

Break-even situation

|

|

Vurdering av behov og handlingsrom

|

Assess needs and flexibility

|

|

Internet/eksternt

|

Internal/external

|

|

Stillingsstørrelse

|

FTE percentage

|

|

Stillingsbeskrivelse

|

Job description

|

|

Hel/oppdelt

|

Full-time/split

|

|

Som planlagt?

|

As planned?

|

|

Tilgjengelig kompetanse

|

Available competence

|

|

Faktiske og kommende krav fra ansatte

|

Actual and future employee needs

|

Our data show that many local authorities almost advertise jobs on autopilot, which can be tantamount to autorepeat. Managers are happy to advertise vacancies without considering alternatives, thereby continuing with the staffing plan they are likely to have inherited from previous managers.

The existing staffing is based on a calculation of how many personnel with different skills are needed to perform the services in question. User needs also come into play. As the services included in this study will predominantly be performed around the clock, the staffing plan will need to cover evening and night shifts in addition to day shifts, both on weekdays and at weekends. With limited financial resources and a large proportion of staff not wanting to work more than every third or fourth weekend, clear guidelines have been put in place for staffing plans.

Working together to advertise jobs

Once the need has been identified and options have been clarified, the next step is to decide whether the position is to be advertised externally or internally, or whether it will serve the purpose of extending the hours of one or more part-time employees in the department.

Collaboration between service managers, HR contacts and trade union representatives is useful for ensuring that the correct procedure is being followed and that the text is designed to attract the applicants that best meet the department’s needs (Moland & Bråthen 2012a). This collaboration is also a good way of ensuring that the job being advertised supports the goal of developing a culture of full-time working. Ideally, this collaboration should continue in the interview stage in order to avoid short-term objectives getting in the way of long-term goals. This refers in part to the negotiation of hours and weekend shifts where applicants want a reduction and managers might be inclined to agree to these out of fear that the applicant will drop out. It also refers to the many ‘firefighting appointments’ due to a department’s desperate need for staff. The latter example is one of the major sins of omission in the local authorities’ HR administration, and has led to non-strategic recruitment and subsequent claims.

Local authorities that advertise and recruit for full-time and near full-time positions

Six (21) points are listed below that describe measures used to a greater or lesser extent by local authorities that work systematically to recruit and retain employees in full-time or near full-time positions.

1 Devise a full-time strategy, politically anchored in short-term and long-term goals.

a) Social partnership, both strategic and operational (practical).

b) Strengthen employer policy by taking a holistic approach to the efforts in full-time working, skills enhancement and reducing absenteeism.

c) Ensure that policy decisions, strategic plans and procedures are in place to design and promote full-time and near full-time positions, which recruitment managers can rely on in their work.

d) Formulate goals and procedures for recruitment practices where there is a requirement for more full-time or near full-time positions and a higher proportion of external job advertisements?

2 Efforts related to attitudes of managers, other employees and trade union representatives.

a) Competence development that gives managers a professional and ‘cultural’ understanding in order to practise the full-time working norms in recruitment and organisation.

b) Information on the benefits of full-time and near full-time positions, improved services and a sustainable working environment.

c) Challenge old habits and ideas, cf. job advertisements with decimal FTE percentages.

3 Financial competence and scope for flexibility.

a) Conduct financial analyses of existing and alternative staffing arrangements, including overtime and extensive use of temporary staff.

b) Give managers more flexibility in terms of finances and recruitment, and the confidence to use it.

4 Offensive job advertising practices based on needs analysis.

a) Work on the text of job advertisements. Seek opportunities to expand, often taking small steps.

b) Do not blindly follow existing shift patterns and calculations in shift planning software. Avoid advertising jobs on autorepeat.

c) Be firm in negotiations with applicants who want to work fewer hours than are advertised, and avoid advertising jobs in a way that lures applicants in.

d) Use a quality assurance loop in collaboration with HR that calls for full-time job advertisements. The quality assurance loop should also include trade union representatives.

e) Assess whether more vacant nursing associate positions can be advertised externally.

5 Review staff leave practices and practices regarding reduced working hours.

6 Improve the service organisation and staffing plans (for full-time and near full-time positions).

a) Use the annual planner/calendar planner regardless of which roster-related measures are used.

b) Use long shifts that allow for large increases in full-time positions.

c) More weekend working for staff in full-time and near full-time positions.

d) Utilise resource units with qualified full-time staff (not pools of temporary part-time staff and zero hours workers).

e) Increase collaboration on staffing solutions across departments and service areas.

f) Anticipate staffing, based on analyses of actual staffing needs for a whole year. This includes projections of holiday leave and sick leave etc.

g) Competence development for managers and trade union representatives that enables them to plan and implement technical measures for full-time and near full-time positions.

Small steps with modest results is a good start

The municipal health and care sector advertises a large number of full-time, part-time, permanent and temporary positions every month. The demand for labour is more or less acute. Many of the measures listed above are extensive and time-consuming. Some require political decisions, considerable amounts of training, and laborious efforts in changing workers’ attitudes. However, these are all necessary to achieve the objectives of the culture of full-time working. In parallel with the long-term work, some measures can be implemented more quickly, with good or moderately good results.

Offensive job advertising practices, quality assurance loops and better leave practices

Point four concerning offensive job advertising practices and point five on staff leave practices are the most relevant to advertising jobs. The process can start with a systematic needs analysis and an assessment of whether a mandate is available to expand a part-time position, prior to the post being advertised. The requirement for an advertised full-time position to lead to a full-time appointment can also be tightened up.

Quality assurance loops

The local authorities will often have dedicated and competent HR staff and trade union representatives who can assist the line managers in the recruitment work and ensure that ‘no stone is left unturned’, whereby more positions are advertised as full-time posts (quality assurance loop). This is a good start that needs limited preparation.

The recruitment and competence efforts as part of the focus on full-time working

If the local authorities have not already done so, it is important to formulate, formalise and establish goals and strategies for a focus on full-time working that can pave the way for more full-time jobs being advertised (point 1). This work should be carried out in parallel, or as soon as possible. Understanding how the efforts in recruitment, competence development, sick leave and the culture of full-time working are interconnected can be both stimulating and cost-saving.

Slightly more binding full-time formulations

A number of strategic and practical formulations describe how local authorities can create more full-time positions and near full-time positions. The smoothly worded rhetoric that positions should preferably be advertised as full-time positions is well known. Here we are looking for a formulation that could make the intention of advertising full-time jobs slightly more binding.

More external job advertisements

As reflected in the job advertisement statistics, far more full-time positions are advertised for registered nurses than for nursing associates. This must mean that establishing mandates for full-time registered nurses and other graduate occupations is easier or a higher priority than for nursing associates. We therefore also call on the local authorities to express and follow up on the intention for more nursing associate positions to be advertised externally.

Managers’ attitudes and scope for flexibility

The development and maintenance of the strong culture of part-time working in the health and care sector has a variety of complex explanations, including the attitudes and values of politicians, managers, employees and trade union representatives. Very often, both in this study and others, the employees’ reluctance to work full-time or increase weekend working is cited as perhaps the biggest problem. There are employees who for various reasons choose to work part-time and who do not want to work longer hours, and there are full-time employees who do not want more weekend hours. However, the attitudes of many managers and politicians to the full-time working issue are just as great a challenge for progressing the efforts on full-time working.

Many local authorities report that their financial situation requires them to reduce the level of expenditure. Local authorities that have decided that they want to work towards a culture of full-time working nevertheless try to increase the hours in one or two positions. Local authorities that have not made such a decision often use the financial argument to maintain the current organisation and culture of part-time working.

Politicians and administrative management in many local authorities consider full-time and near full-time positions to be costly, and do not therefore support measures for a culture of full-time working, even though in general they consider full-time positions to be important for the quality of service. There is thus a perception in the local authority that a culture of full-time working would probably be nice, but is too expensive to implement.

Support for line managers to take risks

Local authorities spend millions on temporary staff, and considerable time administering this. Absence due to sick leave, holiday leave and other activities is fairly predictable at about 20 per cent. The large gap between planned and actual staffing levels shows that this could be handled better in most local authorities. The gap leads to increased use of unskilled labour. Additionally, many managers lack the flexibility to finance larger FTE percentages by ‘borrowing from the temporary staff budget’ to increase the basic staffing level and the employees’ hours.

Resource arguments for part-time working

Resource arguments for part-time working are that part-time employees are familiar with the department and constitute easily accessible reserve labour. This can reduce the need to hire staff externally to cover extra shifts. When part-time employees take extra shifts, they only receive their regular rate of pay because these are classed as extra hours. When full-time employees take extra shifts, they are often paid overtime.

Part-time employees work the number of hours that correspond to the part of the shift roster (there may be an existing mandate) that needs to be covered. This ensures compliance with the department’s allocated wages budget. Part-time employees often work at least as many weekends as full-time employees. Thus, two part-time employees can cover twice as many weekends without compromising either the formal working hour regulations or the usual practice of not working more than every third weekend.

Resource arguments for full-time working

The general resource arguments for full-time working are that full-time employees are dedicated to their work, they are familiar with routines, colleagues and users, and can therefore work more systematically and independently. With full-time employees, managers get a smaller and more manageable staff group. Both managers and senior staff can spend less time on administration, training, supervision and controls. This can free up time for management and for user-oriented activities.

The extra available time and smaller and more competent staff groups will likely make it easier to develop the services. With fewer personnel to manage, the HR departments will also have more time available. Hiring temporary staff, especially from temping agencies, is expensive. More robust staffing plans would reduce the need for bringing in temporary staff.

Service organisation, staffing plans and job advertisements

In order to be able to advertise significantly more full-time positions, local authorities need to implement major organisational and roster-related measures. This cannot be done until the measures under items 1, 2 and 3 have been implemented. This involves overarching political and administrative decisions, close social partnerships and extensive efforts on attitudes that pave the way for change in managers, other employees and trade union representatives. In addition, technical and cultural competence that can facilitate change also needs to be developed (point 6).

Weekend again

Yearly shift rosters, calendar planners, collaborative rostering, pools of temporary staff, resource units, hours banking, increased basic staffing level/pre-emption, fixed and unrestricted hours, combined working, task shifting, fluid staffing solutions and long shifts are all small steps that can be taken to achieve a culture of full-time working. The measures are also important as a basis for advertising more full-time positions. However, their effect is limited if the services are provided both on weekdays and at weekends. Local authorities must either change the prevailing practice of weekend shifts, or increase staffing levels dramatically. The latter will lead to costly overstaffing on the weekdays.

Both managers and trade union representatives are faced with the weekend problem when trying to justify why they do not advertise more full-time positions and in their explanations of why full-time positions are split into smaller positions. This happens because most full-time positions are set up with too few weekend shifts. If a full-time position is to have a sustainable shift pattern, it must be set up with around 325 hours of weekend working. If the number of weekend hours is lower, this must be compensated for by part-time employees (Moland 2021).

To help develop a culture of full-time working, the number of purely weekend positions must first be reduced. The services should then be organised so that fewer employees work only on weekdays. Thirdly, rosters must include more positions with more hours of weekend working. This can be done by scheduling work for more than every third weekend or by extending the length of the weekend shifts. If the latter is implemented, working every third or fourth weekend will be sufficient.

Good services and a sustainable working environment

Long shifts and more hours at the weekend in the course of a year are among the measures that will most effectively enable local authorities to create more full-time positions. Both of these measures have been met with considerable opposition, including from employees who consider more full-time and weekend working to be at odds with a good work-life balance, and trade union representatives who believe that the measures create an unacceptable working environment.

We have cited 16 studies whose findings show that long shift patterns can work well, and often better than the traditional system of 7–8-hour shifts. This is assumed to be because the long shifts in these studies are organised in a way that better balances working hours and intensity than the traditional shift patterns. The question of what constitutes a sustainable shift pattern cannot be answered by looking at shift length and staffing factors alone; both can be important indicators of workloads, but other elements are at least equally important.

When a department is drawing up a staffing plan, the number of full-time positions that can be created is not the only factor that needs to be considered. The following questions can be asked (more often) when a department is reviewing old and new staffing plans:

- Is it user friendly?

- Is it cost-effective?

- Does it comply with the regulatory and legal framework?

- Does it promote a sustainable working environment?

- How many full-time positions are possible?

- What is the highest average FTE percentage that can be achieved?

- Does it appeal to employees?

- Does it appeal to managers?

- Will it attract potential job applicants?

- Does the shift pattern facilitate the ‘ideal shift’?