What is the real cost of full-time working?

-

English summary of Fafo-rapport 2023:22

-

Leif E. Moland, Maja Tofteng og Ketil Bråthen

-

16 August 2023

The financial costs and benefits of developing a culture of full-time working in municipal health and care services

The following is a brief summary of the report. A fuller account can be obtained by reading the summary chapter at the end of the report. Documentation and references can be found in chapters 1–6.

It has already been shown that a culture of full-time working leads to improved services, more efficient operations and a better working environment. It also promotes equality and equal pay. The benefits for service users, employees, employers and society as a whole are considerable. Central authorities and the social partners have carried out several national initiatives and other measures to help local authorities increase part-time hours, and a few hundred local authorities have initiated local trials. Developing a culture of full-time working in municipal health and care services has nevertheless proven to be challenging. There is strong resistance, not from the service users, but from many managers and staff. And the question often arises: Can we afford to invest in a culture of full-time working?

Trying to achieve full-time working is challenging

Many local authorities have tried for many years without achieving the desired results. There are three barriers in particular that stand in the way: many employees do not want to work longer hours, many do not want to work more at weekends and many managers and politicians think it is expensive or not worth the effort.

Longer part-time hours and more full-time workers

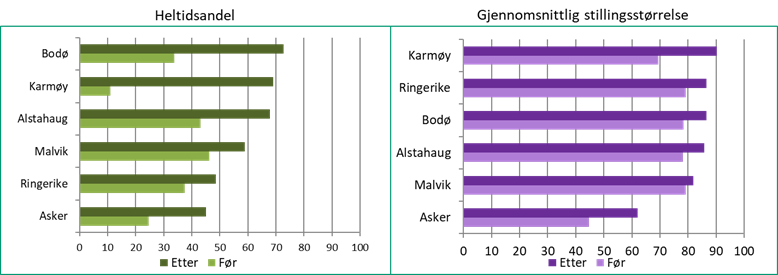

In this report, we follow six service locations in the municipalities of Alstahaug, Asker, Bodø, Karmøy, Malvik and Ringerike. Over a period of two to four years, all of these have dramatically increased full-time equivalent (FTE) percentages and the proportion of full-time workers.

Figure S.1 Increase in proportion of full-time workers and average full-time equivalent (FTE) percentages at six service locations in six municipalities. Source: Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS)/PAI Register.

Translations: Heltidsandel = Full time workers. Gjennomslittlig stillingsstørrelse = average fulltime equivalent

Full-time as the norm, but 80% FTE is also good

This study has confirmed previous research indicating that it may be wise to focus on workers who enable continuity, i.e. those in 80% FTEs or more. This applies when an employee does not want to work full-time and the employer finds it acceptable for them to work fewer hours. In addition to the fact that these workers perform well, it is also easier to recruit multiple part-time employees up to this percentage rather than pushing for full-time working. In practical terms, it is easier to draw up shift rotas when some personnel work 80% as opposed to everyone working full time. This approach also leads to the creation of more jobs, which in turn means that the service location is better placed to manage unexpected absences. This can also have financial benefits. The study confirms our hypothesis that the last 20% of FTEs would be the most expensive to fill.

We have assumed a uniform need for services for all weekdays. Service locations with a reduced service provision at weekends will be able to develop a culture of full-time working with lower costs.

Full-time working can be pursued through costly or cost-effective means

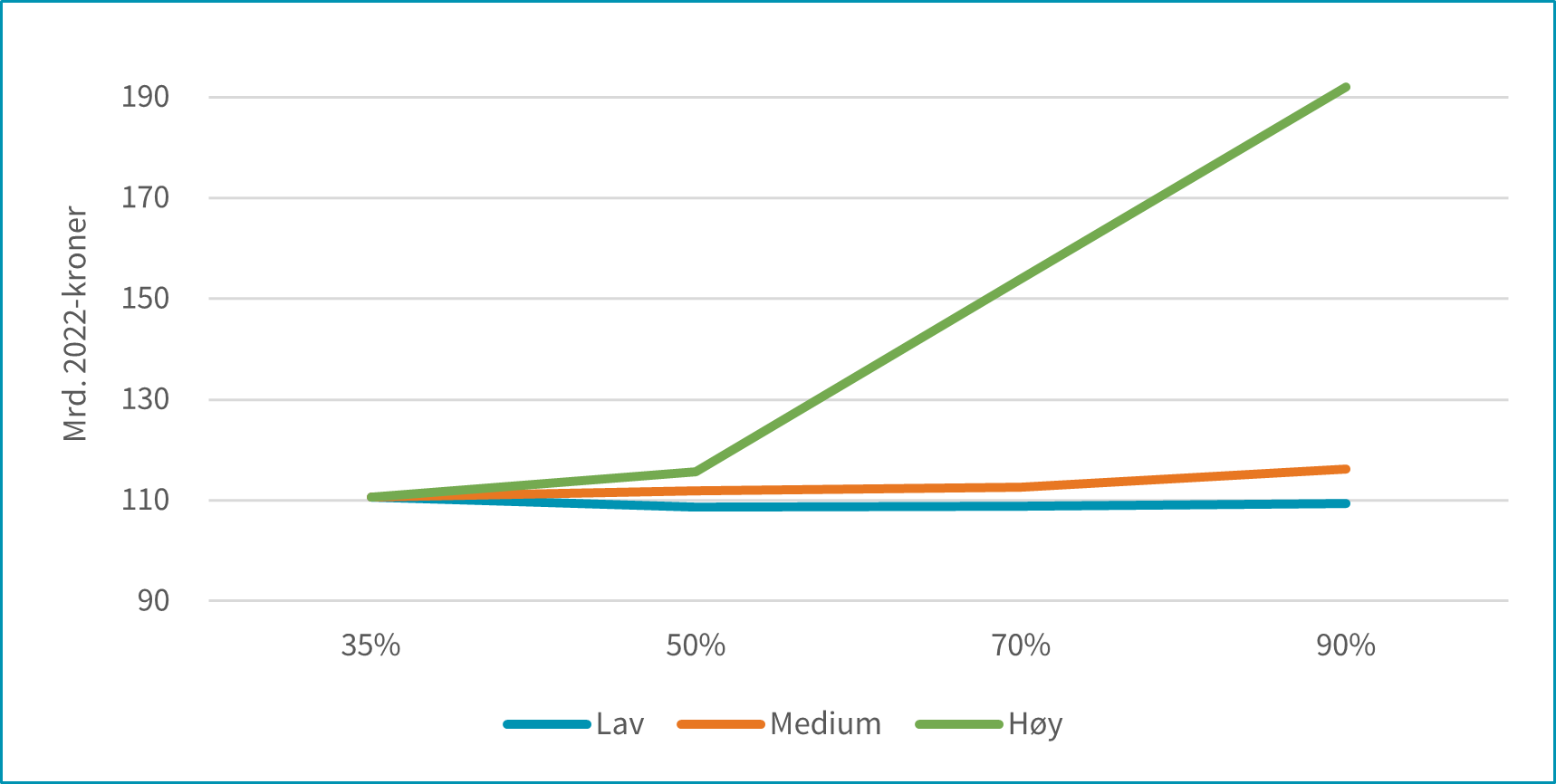

The various data sources show that the aim of increasing the proportion of full-time workers can be achieved in different ways. We have established three theoretical models to illustrate the economic effects. The most expensive approach (referred to as ‘High’ in the figure) is to continue with the ‘traditional’ shift pattern involving seven–eight-hour shifts and working every third weekend. This model is costly because it increases FTE percentages without a corresponding reduction in the number of employees. This is a result of the fact that too many permanent employees do not work enough at weekends.

The more cost-effective approaches (referred to as ‘Low’ and ‘Medium’ in the figure) involve increasing FTE percentages while also reducing the number of employees. This requires varying degrees of reorganisation in terms of duties, skill composition and staffing plans that cover annual shift rotas and long shifts.

The focus on full-time working is funded by investing variable financial resources for labour (e.g. for temps and extra help) in permanent, full-time/near full-time positions. Most local authorities have variable wage costs of around 20%.

Details that impact on cost levels

The shift pattern is the single factor that has the greatest impact on labour costs. This is followed by several other cost elements, partly as a result of the shift pattern chosen and partly due to other factors: the skill composition within the staff group, use of extra help, overtime, weekend supplements, recruitment measures, paid breaks, scope of recruitment, time for training and guidance, duplication of effort and possibly sick leave. In addition, there are costs that are not included in the service location’s accounting, such as HR administration, insurance and pensions.

Effects on society

We have estimated the societal effects of increasing the proportion of full-time municipal care sector employees based on three different models: Low, Medium and High. A full-time working approach in line with the most expensive model could lead to costs for wages and temporary staff almost doubling, from NOK 110 billion to NOK 192 billion. In contrast, when working hours are increased in line with the more cost-effective models, the cost development is very modest.

Figure S.2 Total wage costs and cost of temporary staffing with different proportions of full-time workers. In NOK billion as per 2022. Different models. Municipal health and care sector.

Translations: Mrd. 2022 kroner = NOK billion as per 2022. Lav = low. Høy = high

Smaller staff groups and familiar employees with the right skills

The study presented in this report confirms previous studies of the relationship between full-time/near full-time positions, enhanced competence and improved service quality. Having fewer service providers interacting with service users and more familiar professionals working at weekends are increasingly highlighted as both a desired and observed effect of increasing part-time hours.

Analyses of patient-oriented needs and staffing requirements lead to a reorganisation of tasks, which in turn creates opportunities to establish positions with longer part-time hours. Better alignment between planned and actual staffing reduces the extensive use of unskilled workers in shifts that require healthcare professionals. Improved utilisation of planned personnel can enhance service quality, even when the new staffing plan has fewer university-educated employees than the previous one. This is a result of more effective utilisation of qualified personnel.

Local authorities should have the financial means to fund a culture of full-time working

The main finding in this report is that the effort to increase part-time hours has gone hand in hand with the improvement in staffing plans. This has led to better use of human resources and more efficient services. We have seen several instances where service locations have designed new staffing plans that minimise the additional costs of increasing the proportion of employees in permanent full-time or near full-time positions.

Some service locations in this study have made more progress than most of the others in the push for full-time working. This is not a result of increased wage costs but is due to staffing analyses and the development of new expertise in drawing up shift rotas. The question that local authorities, therefore, need to ask themselves is whether they can afford not to invest in a culture of full-time working.