Sector-specific policies for older employees

-

Engelsk sammendrag av Fafo-rapport 2022:21

-

Tove Midtsundstad, Anne Inga Hilsen og Kerstin Nilsson

-

01. februar 2023

This report summarises, specifies and evaluates the challenges and possibilities of retaining more older employees for longer in ten different industries. The objective is to identify what is universal and represents general challenges in the workplace, and what is specific to particular sectors in terms of challenges and possibilities. The industries included are the manufacturing industry, the retail industry, passenger transport, the financial services industry, academic professions in the private sector, preschools, the nursing professions in the hospital sector, the education sector, healthcare services and government administration.

The report is based on the swAge™ model and explains the status and changes in framework conditions regarding policies for older employees and the position of older people in the labour market. The report discusses how societal developments affect the industries and create challenges and possibilities that are both partially similar and different. Six general workplace strategies related to policies for retaining older employees are described and discussed before examples of specific workplace strategies and measures for each individual industry are presented. In the conclusion, knowledge about which processes, strategies and tools might be suitable to use at a local level in order to succeed with policies for retaining older employees is summarised.

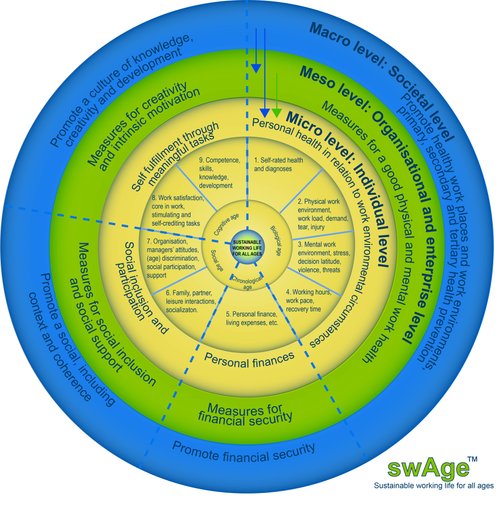

The swAge™ model

A range of factors influence whether employees can, want to and are able to work until reaching a higher age. These are well summarised in the swAge™ model (Nilsson, 2016), a theoretical model developed on the basis of previous research, theories and recent empirical studies within areas such as work organisation, occupational psychology, ergonomics, gerontology, occupational medicine, pedagogy, economics, discrimination and health factors in working life.

The swAge™ model has nine different areas of influence and decision-making, which all have a bearing on sustainable working life for people of all ages. In the model, these areas are seen from the perspective of the individual employee, the organisation/business, and society. The model visualises the complexity of working life.

The circle in the model is further divided into four spheres that represent the central areas that are decisive for the individual’s employability: the working environment’s impact on personal health; relations, support and social inclusion; personal finances; and the performance of tasks and activities at work. These four spheres are also the same that individuals, more or less consciously, take into account and consider when they are deciding whether to continue to work or leave a workplace. The four spheres in the swAge™ model are also related to four different ways to define age: chronologically, biologically, socially and cognitively, respectively.

All societies, industries, workplaces, occupations, tasks and individuals are different. Nevertheless, all nine areas of influence and decision-making must be functioning effectively in order for working life to be sustainable. However some areas can be of more significance generally, while others will be more specific to particular industries, workplaces and/or individuals, precisely because societies, industries, workplaces, occupations and individuals are all different and have different problems and challenges. Our metastudy uses the swAge™ model as a theoretical basis for the descriptions and analyses.

Framework conditions, trends and common challenges

Demographic developments, changes in working life and in the labour market, changes in the economy and living conditions, and changes to legislation and the system of agreements affect all industries and occupational groups.

Demographic developments

The population and the workforce are ageing. It is therefore important that more non-working and older people can and want to work for longer to meet the need for labour. Increased life expectancy and better health among older people also make this more realistic. The same applies to the increase in the population’s education level, as people with higher qualifications continue to work until reaching a higher age. However, although most older people are healthier, there are significant differences between people with different education levels and occupational groups. Even though more people are pursuing higher education, the majority still have only a lower or upper secondary school education. Most older people are therefore employed in traditional manual occupations or in the service, health and care professions, and few of them are still working full-time after they reach the age of 67.

Changes in financial and living conditions

The living standard of the population has steadily increased over recent decades. The majority of people who are approaching retirement age are in a sound financial situation, are free of debt, own their own homes and have savings, investments in equity funds or other securities. Therefore, many people can afford to retire early if they want to, even if the pension is reduced. At the same time, there are a number of people who are struggling financially. Income and assets are unevenly distributed among older people. Therefore, some people continue to work because they need the income to get by financially. Personal finances and prosperity therefore have an impact on the retirement pattern and are significant in relation to how economic incentives in the pension system work.

Changes in working life

The demands for competence in employment in Norway have increased. At the same time, the proportion of labour-intensive jobs that do not have higher education requirements has increased, while jobs that require medium-level qualifications, such as skilled industrial work and commercial occupations in offices, trade, banks and insurance have decreased or stagnated due to technological changes.

Therefore there is good reason to pay special attention to the digitalisation trend, as this will influence most jobs – many will change and some will disappear, in parallel with the development of new jobs. Which industries require labour and which qualifications are in demand will consequently change, as will the needs for downsizing, upgrading skills, retraining and further education.

International comparisons otherwise show that Norwegian and Nordic working life still scores well on working environment indicators and on autonomy, trust and employer/employee relations. However, there are also reports of increasing work intensity, and the strain of high performance requirements and low levels of autonomy often affect occupations and industries differently.

The pension reform

The pension reform has changed both pension benefits and opportunities for early retirement. It is currently possible to receive the National Insurance Scheme retirement pension, the contractual early retirement pension (AFP) and occupational pension when one reaches 62 if earnings and the required pensionable service time is sufficient, but the annual benefits will then be lower. In addition, the life expectancy adjustment will gradually contribute to comparatively lower benefits at the same age.

The contractual early retirement pension (AFP) has been converted to a supplementary occupational pension scheme for all pensioners who have a right to AFP. It is no longer restricted to those who retire between 62 and 67. Those who receive the pension can, in addition, work as much as they want to without the pension being reduced. The rules for pensionable service time have also changed, so that every Norwegian krone earned and every year worked after turning 13 count up to and including the year one turns 75. In addition, from 2006 all employees were given the right to a occupational pension from their employer. There are, however, significant differences in what employees can expect to receive in benefits from these schemes.

All of the changes mentioned apply to employees in the private sector, but they have not been fully implemented yet for employees in the public sector. The pension reform has not been concluded either. The pension reform committee has recently proposed raising the age limit for drawing a retirement pension from 62, and the limit for the pensionable service time from 75. The intention is to prevent the life expectancy adjustment from giving rise to insufficiently low pension levels for early retirees. The higher age limit is expected to change the norm for when it is considered natural to retire and cause the number of older people in the workforce to increase. The proposal has not yet been adopted, but it has wide support among the party representatives in the pension reform committee.

So far, the reform has resulted in increased workforce participation after the age of 62. The proportion of older workers with occupational health problems working after the age of 62 has also increased, as the possibility to retire early with a good pension has been diminished. In 2018, it was agreed to establish an early retirement pension supplement (slitertillegget) to address the problems of those who (need) to retire early due to long careers and demanding work conditions and have no other form of income. Expansion of this scheme is under discussion. It is, however, unclear if and when that will happen, and how such a change is to be formulated and financed. The special age limits, which for example encompass large groups of nursing staff in hospitals and healthcare services, are also going to change. A committee has drawn up a model for adapting to a new public pension, but there is still some way to go before this is finalised.

Agreement for a more inclusive working life

Like the pension reform, the Agreement for a more inclusive working life has, since 2001, had the goal of getting more people to remain in employment for longer. However, the efforts of enterprises to invest in older employees have been lacking, especially in the private sector. Moreover, few of the most common measures chosen by the enterprises have been shown to have a demonstrable effect on the employment of older people.

A new Agreement for a more inclusive working life was introduced on 1 January 2019, with the aim of reducing absence due to illness and expulsion from the workforce due to long-term sick leave. The new Agreement does not mention older people or their participation in the workforce. Furthermore, it has been expanded to apply to all Norwegian enterprises, and it is no longer a prerequisite for enterprises to sign a local agreement to be party to the Agreement. This may diminish the possibility to sanction enterprises that fail to fulfil their obligations. Local union representatives also lose the option to withdraw their commitment to the Agreement if the enterprise does not comply with its obligations. Preventive and motivational efforts to increase the participation of older people in the workforce may also have been affected, as there is no longer a focus on this in the Agreement or by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration’s advisers. The Agreement will be renegotiated for 2023, and from the viewpoint of older employee policy it is especially important to see how this area is safeguarded in the revised Agreement.

The Working Environment Act

Norway has one of the highest age limits for employment protection in Europe. It was 70 until the end of 2016 and is currently 72. There is also debate about what the age limit should be and whether there should be an upper limit, as more people are fit and healthy and want to work for longer, and should be allowed to do so. The counterargument is that there are few people today who work after turning 70 and it is more important to get more people to work until they are 67. There is a fear that a further increase may lead to more degrading routines in which older people who can no longer cope with their job must be told it is time to retire. The objection that carries the most weight is, however, the increased use of the lower internal age limit of 70 for businesses since 2015. Therefore, fewer enterprises in the private sector retain employees after they have reached 70, as everyone must give up their ordinary position when they reach the age limit in an internal retirement scheme. Incidentally, this is also the situation throughout the entire public sector. As a compromise, the Holden Committee (NOU 2019:7 Work and benefits – Measures to increase employment) proposed an age limit of 70 for everyone while simultaneously phasing out the internal age limit. Although this lowers the upper age limit, it gives enterprises the option to allow certain individuals to continue after turning 70. In this way, one avoids ‘throwing the baby out with the bath water’, as the amendment in 2015 did to a certain extent.

In 2008, an amendment was made to the Working Environment Act, and employees were given the right to work part time on turning 62, on the condition that this was possible in the place of work. Nevertheless, part-time employment has not become more common among older employees in the private sector, at least not before they have turned 67. Four out of ten employers in the private sector claim that it is very difficult to meet the wishes of older employees for reduced working hours. The possibility of working part-time was also lowest in industries and businesses with the highest rates of absence due to illness, incapacity and early retirement — in other words, industries where one might assume that the need was greatest.

Similarities and differences between industries

As the swAge™ model shows, the individual’s capacity, desire and opportunity to work longer is affected by different societal factors, conditions at the organisation level, as well as by individual factors and conditions in the private sphere. The report describes briefly how general development trends and framework conditions affect the ten industries under analysis.

The effects of the demographic changes

Even though all industries must respond to the demographic changes, with labour shortages expected in the future, the recruitment challenges vary. While the hospitals have an acute lack of registered nurses, especially specialist nurses, the municipalities lack registered nurses, auxiliary nurses, qualified school and preschool teachers, and the bus industry has difficulties obtaining enough drivers, the problem in the financial services industry is completely different. In the retail and manufacturing industries there are no widespread recruitment problems either. In relation to academic professions in the private sector and government administration, recruitment problems vary according to the specific skills and qualifications required.

In addition to affecting the labour force available, the demographic changes will also affect the demand for labour in different industries in different ways. A greater number of older people, for example, increases the need for more employees in healthcare services and in the hospital sector, while the decline in birth rates will, in the future, reduce the need for employees in preschools and schools. Considered in isolation, a general increase in the population and investment in public transport as a result of climate change issues will also change the demand for employees in passenger transport.

The effects of technological development

The greatest driver for changes in labour requirements and competence is technological development. Increased robotisation, automation and digitalisation changes the content of work, as well as the requirements for skills and organisation. The working population must therefore be willing and able to adapt to new requirements and new working methods. This also applies to older employees. At the same time, new technology has helped to ease, simplify and even eliminate the burdens of work, and in this way contributed to more people being able to keep working for longer. In several industries, it has also led to a reduction in the need for labour.

Technological change affects industries and occupations differently, depending on whether the job involves working with ‘symbols’ (as in the financial services industry, government administration and in academic professions in the private sector), ‘production’ (as in the manufacturing industry and goods transport) or ‘people’ (as in education, hospitals, healthcare services, preschools, passenger transport and the retail industry).

Of the ten industries, digitalisation has, in particular, affected the demand for labour in the financial services industry; here, the number of employees has been significantly reduced with the aid of redundancy packages. In the manufacturing industry, automation and robotisation have also reduced the need for labour, but have at the same time eased and eliminated heavy and strenuous physical work, as many manual operations have been replaced by robots and computerised production processes. With the development of self-driving cars and the increased use of drones, the need for drivers in passenger transport may also be reduced in the future, even though security considerations and passenger safety might mean that bus, train and metro conductors will still be needed. The same tendencies can be seen in the retail industry, in which self-checkouts mean that repetitive work in a checkout is replaced by more service-oriented work and customer guidance.

Developments are different in preschools, hospitals, schools and healthcare institutions, as the tasks cannot be carried out so easily through automation and the need for services is to a great extent driven by demographic changes. Therefore the changes have primarily affected the type of tasks, the organisation of work and competence requirements, and partially reduced some work burdens, while some new ones have also emerged. Digitalisation has, for example, made more reporting and documentation possible and increased availability outside of normal working hours, but also increased flexibility in relation to workplaces and opened up the possibility of working from home. Technology is also being used increasingly in monitoring and surveillance, which can provide increased security but also increased work pressure and stress.

Increased demands for efficiency

Although the working environment has improved in a great number of areas over recent decades, studies of industries show that other working environment problems have emerged and gained increased significance. This applies especially to psychosocial and mental pressures, such as increased stress connected to staff reductions or staffing levels that are too low, increased demands for efficiency, more documentation and reporting, more control and less autonomy. In other words, more factors that mean having to do more than before within the same working hours and with the same number of staff, but with less self-determination. Many mention therefore that hustle, stress and a guilty conscience about everything they do not get done are the main problems. In addition reduced autonomy and more control systems and detailed management of work tasks is mentioned, in particular by employees in government administration and the other public sectors we are examining, but to a lesser extent by employees in the private sector. Many researchers specialising in working life relate this to the introduction of what is often termed New Public Management in the public sector, which gained impetus from the mid-1990s.

The significance of the pension reform

The entire workforce is affected by the pension reform, although the rate of change is slightly different between the public and private sectors, and the reform is still in its initial phase. The pension that employees can expect to receive and the age at which they are allowed to retire varies. Most of those working in the public sector can expect a reasonable pension and can retire at the age of 62. In the private sector, however, retirement benefits and the option of early retirement vary considerably. Those who have a high level of education have access to better retirement schemes and a greater degree of choice than those with a low level of education. People working in the financial services sector can, for example, expect to receive a large pension, as they have had access to an contractual early retirement scheme (AFP) and occupational pension schemes for a long time, while employees in the retail industry often lack both AFP and a good occupational pension scheme. Therefore, many of them will not have the right draw a pension at the age of 62. Older employees in the manufacturing industry are situated between these two extremes, as most of them have a right to AFP and the option to draw a retirement pension at the age of 62, although most occupational pensions are minimum schemes for many of them.

The life expectancy adjustment will have the greatest impact on employment in the long term, as more people will have to work until reaching a higher age to receive the same pension as today, or accept a lower pension. This will be easier to achieve for highly qualified employees in government administration and academics in the private sector, who started later in working life and have occupations with fewer burdens, than it will be for assistants working in preschools, nurses, process workers in the manufacturing industry, drivers and employees in the retail industry. At the same time, flexibility has increased so that more people can combine employment and the pension without a reduction in their income. There are many people that do this also a few years after turning 62. This applies especially to men in manual occupations in the private sector, such as the manufacturing industry and the bus sector.

It also appears that more people than before can envision doing some work after retiring from regular employment. For employers, an extra workforce of flexible pensioners who are willing to work will be extremely beneficial in dealing with fluctuations in labour needs. But a greater supply of pensioners, who have a kind of universal basic income with the pension, may also contribute to undermining wages and working conditions in certain sectors/occupations. If a large enough number of pensioners are employed on fixed-term work contracts at a lower rate of pay after reaching the retirement age limit, as is usual in a number of industries, this may have the same effect.

The effects of the Working Environment Act and the Agreement on a More Inclusive Work Environment

The age limits for employment protection determine how long a person can work. At present, almost half of the employees in the private sector and all employees in the public sector must terminate their regular employment on reaching the age of 70. In the private sector, a lower internal age limit for businesses is most widespread in the financial services sector and within technical and scientific service providers, but it is relatively uncommon in the retail industry. This seems paradoxical, as the conditions for being able to work until reaching a higher age should be more favourable within the financial services sector and various academic occupations in the private sector than they are in the retail industry. On the other hand, the retail industry has many part-time positions that may be better suited to older employees who want to reduce their working hours or take on an extra job or small engagement, which it appears that many people over the age of 70 would like to do.

The Working Environment Act contains provisions for adapting work conditions and a conditional right to work part-time after turning 62. Consequently, a large number of workplaces offer a range of adaptive measures for workers, including older employees. In general, however, it is easier for older employees to get a reduction in working hours and be provided with adaptive measures in the public sector than it is in the private sector, and easier if a person works in a higher education institution, an academic occupation or an office job than if they work in the manufacturing industry.

Endorsement of the Inclusive Work Environment Agreement’s various objectives and efforts to promote policies for retaining older employees also varies between industries. The private sector has the lowest proportion of policies and measures directed at retaining older workers, where interest also diminished after the pension reform. Interest is especially low in the retail industry and business services. The changes seem to be partly related to the pension reform, which led to increased participation in the workforce, and also to the Agreement, which has since 2018 no longer emphasised policies directed at older employees.

In the public sector, policies and measures for older employees have been generally more widespread, although interest has also declined there. In the government sector there is, at least for the time being, a contractual right from the age of 62 to an eight extra days off and the option of being able to arrange for a further six days. Special arrangements for older employees are less widespread in other wage groups, and it is to a greater extent up to the individual enterprise to establish them. Several of the arrangements have also been phased out or changed. This applies to healthcare services and preschools, for example.

Special characteristics of the industries and occupations

Many of the differences between the perceived problems and challenges in industries can be linked to the type of work that is carried out (if it involves working with symbols, production or people) and to whether one employs and seeks employees with a high or low level of education.

Academics and groups of employees in higher education institutions generally have a lower level of absence due to illness and lower rates of incapacitation than employees in occupations that require a lower level of education, and fewer employees in these occupations withdraw from working life in their early sixties. The challenge for industries that employ people with a higher level of education is therefore not primarily to reduce absence due to illness or reduce incapacity and early retirement but to persuade more employees to continue to work after turning 67, and preferably for a few years after turning 70. Those with a higher level of education have a better starting point in regard to the prerequisites for working longer than those with a lower level, as many of them have better health, easier jobs, higher salaries and a higher life expectancy. In general, they have also worked for fewer years when they reach 62, as they started their working life later. Surveys that chart the reasons for taking early retirement show that for people with a high level of education, the loss of motivation for and interest in the job and a desire to coordinate retirement with a partner are more important reasons for retiring than burdensome work and poor health. This applies in particular to academics employed in the private sector and in government administration.

Those with a high level of education often have access to better pension schemes and a better financial situation in general than those with less education, as most of them have had a higher income throughout their career. Consequently, they also have more freedom to choose when to retire. The measures in the new pension system, which primarily punish retirement before turning 67, do not therefore have the same effect on the behaviour of those with a high level of education as those with a low level. It is true that they will also feel the consequences of the life expectancy adjustment, but will not to the same extent be forced to postpone retirement in order to cope financially, as most of them can expect a good pension and they have other financial resources to fall back on.

The exceptions to this picture are registered nurses and people with a high level of education in the municipal sector, such as preschool teachers and school teachers, where the rates of absence due to illness and early retirement are high and partially resemble those found among employees with less education. These are all occupations involving relations with other people, where the mental and, in part, physical work burdens are greater than in other professions. Hospitals, healthcare services and schools have therefore, as employment studies show, completely different challenges than government administration and the academic professions in the private sector. The differences are also gender-related, as employees with a higher education in the municipal sector and nurses in hospitals are for the most part women. The divergent pattern of withdrawal from working life is therefore also about gender differences.

Strategies and options

What can be done to give more registered nurses, health workers, preschool assistants, teachers, employees in government administration, shop assistants, bus drivers, train drivers and process workers the opportunity, the desire and the ability to work for longer than today?

The proposals presented here have a policy perspective focusing on the older employee, as the over-fifty age group has other challenges, desires and options than younger employees. Older employees have more experience and, as a rule, work more independently and therefore require less management in their daily tasks. That does not mean that management is unnecessary; older employees have a greater need to be seen and acknowledged for their efforts because they have a choice. They can simply withdraw from working life for good if they are not appreciated. In addition they can, in the light of their experience and competence, often act as important role models for younger people, and seamlessly and almost free of charge transfer their competence and business-specific knowledge to younger employees and new recruits through their daily work. They also have fewer obligations at home, and therefore may not feel the same work versus family-life pressure that many people experience when they have young children. As such, it may be easier for them to take an evening shift if needed, go on longer work trips, or participate in conferences or courses. On the other hand, they may feel the effects of the burdensome aspects of work to a greater extent than younger people, given that they have been doing it for longer, even though most of them have also shown that they can cope with it as they are still working. Many of them have learned smarter ways to work. They know the rules, routines and procedures, and they have the important contact networks. They have also developed work techniques and ‘tricks of the trade’ that make the job more manageable. They may work more carefully than before to avoid injuries and take less chances, know how to deal with difficult students, customers, passengers and patients, and are perhaps also better able to prioritise the most important tasks when there are many things waiting to be done.

Joint challenges – joint solutions

In the report, a selection of potential policy strategies for older employees are presented that may be suitable for retaining older employees in the face of the perceived cross-sectoral challenges.

Cut to the bone

In almost all of the industries, the increased demands for efficiency were mentioned as a challenge for older employees, although the words used to express this and the accounts of experiences are different. The demands are felt by many to be too great in relation to the available resources and manpower.

Increased staffing levels and more resources come at a cost. Nevertheless, the question that enterprises can ask themselves is what is most profitable in the long run – to employ a couple of extra people or to have the barest minimum of employees but have higher levels of absence due to illness, greater wear and tear on employees and more employees who become disabled or retire early in the future. Sometimes cutting things to the bone can also result in cutting off your nose to spite your face, if current costs are the only things that count, and no consideration is given to the aspect of prevention and the long-term savings made in terms of budgets for sick leave and disability benefits.

In some cases, it would be more profitable from a societal point of view to increase staffing levels if it reduces the amount spent on health and social welfare benefits in the long term. The problem is that this is not always the case at organisation level, in the individual school or preschool and at the individual hospital, as the bulk of expenses associated with long-term sick leave and disability are met at a societal level.

Too many demands in relation to resources is however not simply a matter of the number of people but also about the number of work tasks to be carried out and the organisation of work tasks. The hustle and stress can be reduced by reviewing the task list and reorganising it with this in mind, taking care not to add more tasks without also omitting or downgrading others. Are there any work tasks that can easily be omitted, things that are done for the sake of habit that are no longer necessary, or tasks that can be automated or carried out more efficiently?

With freedom comes responsibility – not responsibility without freedom

Reduced autonomy or self-determination is another problem frequently described by older employees. Micromanagement can impede the individual’s development of, and ability and opportunity to exercise their professional judgement, which will in many cases be crucial for doing a good job. This can rapidly result in a loss of motivation, increased stress and reduced job satisfaction, something that employment studies from hospitals, healthcare services and the education sector also show. Micromanaging the individual’s working day does not provide any space for individual formulation or adaptation of work tasks (job crafting), a factor that has been shown to be important for older, experienced employees’ motivation, sense of accomplishment and productivity. This is better promoted through a personnel policy that clearly signals to employees that there is extended scope for individual participation, involvement and co-determination.

If demands are linked to increased documentation and reporting, one solution may be to let go of the reins and trust that qualified employees will carry out tasks in the way that their profession demands they should be done. This applies in particular to the public sector, especially in areas where the employees are highly qualified and competent. In this context, the ongoing trust-based reform of the public sector could be a useful point of entry, as it is built around a critique of the existing management principles. The perspective of older employees is important in this respect, as increased employee autonomy and the exercise of judgement usually requires experience and professional competence. It is also important that the goals of the service are delimited and clear, and that the accompanying resources are adequate, so that the responsibility for difficult, if not impossible, prioritisation does not fall upon by the employee alone. A clear and supportive management that helps the employees to weigh up the relationship between requirements and possibilities is therefore important. In this context, older employees with long experience have much to contribute, as they will more often have been through similar dilemmas in the course of their working lives and seen the consequences of different choices.

Sustainability and reuse

The terms sustainability and reuse are also suitable for the area of older employee policy, as reuse and renewal of older employees’ competence through further education and retraining can contribute to more people having many more good years in working life, as well as enabling society to gain better access to labour, increased tax revenues and a reduction in welfare costs.

In many cases, it can be more profitable for a business to upgrade and/or retrain one of its older employees than to recruit a new employee straight out of school, as it is not certain that the new employee will remain longer in the business than the older employee due to the far greater mobility of younger people compared to older people. If an employee is struggling in the job they currently have, retraining and transfer to another and possibly easier job in the same enterprise can also provide a solution. However, this will not be possible in all workplaces, and perhaps to a lesser extent in small and medium-sized enterprises, as it not always possible to find alternative jobs.

Two plus two can equal five

The organisation of work tasks – how to put together the work team and competence available in the best possible way – can mean, in effect, that two plus two equals five. Although there is individual variation, older employees with long-standing experience will often bring with them another level of competence than that of younger employees who have come directly from school.

Proficient older employees can often function as instructors and role models for younger employees. By working with and observing how older employees work and carry out their work tasks, younger people can learn good routines and smarter ways to do their work. In this way, older employers can function as oil in the machinery, by giving inexperienced employees necessary training under guidance, as well as being an accessible source of useful information about the workplace, such as the essential rules and routines and the important contact networks for the enterprise. As such, older employees can often contribute to increasing the productivity of younger employees and collectively, that of the enterprise.

To achieve the transfer of knowledge or a suitable composition of teams with different experience and competence, one can either establish formal schemes in which older employees are given the role of instructor, mentor or ‘workplace buddy’, or one can organise work teams or duty teams so that they have a good mixture of employees with different levels of experience.

Management – for better or for worse

In many studies, management has been found to be a key factor in retention or exclusion. Being seen and valued by a manager contributes to the desire to remain employed for longer, while poor leadership can contribute to earlier retirement. Good management is also about taking care of older employees and facilitating long working careers. To enable managers and appraisal interviews to have a positive effect on the working environment and the individual employee, it is necessary to have sufficient time to practise good leadership. That means having opportunities to see, listen to and provide adequate feedback and encouragement when it is needed, as well as the possibility to get an overview of the employees’ competence, knowledge, needs and wishes. The latter is necessary in order to gain maximum benefit from the competence that is available, and it is important to enable the composition of a well-functioning work team. In this context, appraisal interviews will be an important tool, alongside the ongoing contact one has in connection with work tasks.

Giving managers more time and scope comes at a cost, but so too does a lack of good personnel management One should therefore ask whether all of the reporting, documentation and checking routines that managers are required to carry out in many industries today are necessary. It was particularly clear that this a ‘time thief’ in relation to key work tasks and management in the school sector, preschools, hospitals and healthcare services.

It may also be appropriate to discuss what to do with managers that do not function well and perhaps dare more often to relocate poor managers, if one perceives that they contribute to a high level of absence due to illness, a high turnover of staff and the early retirement of employees. The importance of having good recruitment processes in the enterprise is also linked to this, to ensure that managers with the right qualities are hired, as well as placing emphasis on management training, guidance and good following up of managers.

Better to be safe than sorry

Health problems and work stresses are the key reasons for withdrawal from working life and early retirement for older employees. The working environment in many occupations and industries has improved, but a considerable proportion of employees in Norway are still subjected to working environments that are injurious to health. Efforts to prevent muscular and skeletal disorders in particular, which are the main reason for early retirement among older employees, are therefore important to increase the work participation of older people. It is, however, a paradox that we have so much knowledge about factors that have a harmful effect on health and the measures that can help, but we know so little about how to make enterprises use this knowledge.

In addition, we lack insight into the reasons why employees within the same occupation and industry, including older people contra younger, are affected differently by exposure to various working environment factors. For this reason, it is important that managers are familiar with their subordinates, so that they can quickly react if employees show signs of developing health problems to prevent them from becoming a part of the statistics for sick leave, disability or early retirement. In this context, regular appraisal interviews have a key role to play. In addition, it is important to be aware of older employees’ wishes and needs in relation to work tasks, projects and skills development. If one waits until employees are on the verge of retirement to start discussing policies for retaining older employees, they have probably had sufficient time to prepare for this and have already made up their mind to retire. Good policies for retaining older employees are therefore preventive and begin early in the course of a career, creating a path that enables and encourages employees to choose a late retirement.

How to approach this at organisation level

As the review shows, the challenges faced by industries and individual enterprises are different. Which of the large and small measures and tactics that are appropriate to use will therefore vary, not just between industries but also between individual enterprises in the same sector. The same applies to the ability, willingness and opportunity to adopt them. Small enterprises have different framework conditions and challenges than larger ones. They do not have the same resources to deal with problems either. Geographical location will also have an impact, as labour markets and access to labour with the right qualifications will differ.

In general, enterprises in the public sector have been more active than private ones, large enterprises more so than small ones, unionised enterprises more so than non-unionised ones, enterprises with a labour shortage and recruitment problems more so than ones that have easy access to labour, and enterprises with a sound financial situation more so than enterprises that are just scraping by. Enterprises that have policies for retaining older employees also often have an integrated approach to active ageing, and focus on the prevention of health problems and updating of skills throughout employees’ entire careers.

The most common measures offered by Norwegian employers to promote later retirement have been extra annual leave and days off, reduced working hours or graduated pension benefits, and bonuses and salary supplements. The interest in retaining older employees has changed over time, however, and the pension reform with its measures has caused some of the industries and enterprises to revise and adjust their retention policies and schemes. Nor does the offer of special measures and schemes mean that older employees automatically change their behaviour. Analyses show that extra annual leave and days off, and salary supplements or bonuses from the age of 62 resulted in somewhat more older employees choosing to remain in their jobs, but the possibility of reduced working hours with salary compensation have not contributed to extending working careers. There has also been a tendency that such schemes are often found in enterprises with good financial means employing workers with a higher level of education, where there was less need as many already remain in employment until their late sixties. Moreover, measures such as extra annual leave and days off, and salary supplements or bonuses can be said to play on external motivational factors, where the purpose is to entice the individual to continue to work using financial incentives. The alternative for enterprises is to influence the individual’s possibility to keep working by adapting work tasks, reducing demands and/or by enabling the employee to better meet them, for example, by implementing different health and competence-promoting measures.

The enterprise could also attempt to influence the individual’s motivation to work by offering more interesting and challenging work tasks, to show that their competence is valued, and/or to improve the social environment in the workplace. Such measures for preventing health problems and reduced working capacity will also provide a supplement in real terms to the pension reform’s main instrument, which is after all primarily financial incentives: that it should pay to work.

Which tactics are suitable for achieving a good policy for retaining older employees? In the light of previous research, the following factors stand out as especially important:

- Mapping out the age distribution, competence of older employees and the retirement pattern.

- The tool box – which measures one chooses depend on local challenges and needs.

- Clarification of the scope of possibility and allocation criteria for the available measures.

- Mapping of individual employees using the appraisal interview as a key tool.